BLOG

Photo by Emily Scott

Another Decade, Another Decade Dare

Twenty years ago, when I turned 40, I wanted to mark the passage of time with what I called, a ‘Decade Dare.’ The concept was simple; do something completely out of my comfort zone, incorporate my time, treasure, and talent (assuming I could figure out a sliver of some talent) as a fundraiser for a specific organization or cause. Lastly, it would be for something I had not yet requested my friends and family to consider in their generous giving.

This article originally appeared on Medium.com on August 9, 2016.

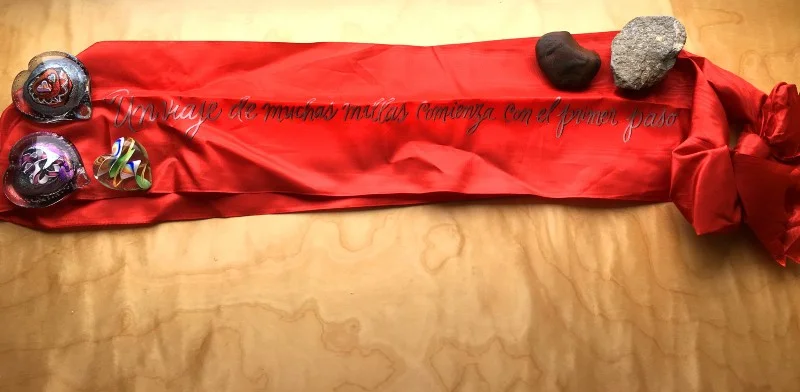

A Journey of Many Miles Begins with the First Step

Twenty years ago, when I turned 40, I wanted to mark the passage of time with what I called, a ‘Decade Dare.’ The concept was simple; do something completely out of my comfort zone, incorporate my time, treasure, and talent (assuming I could figure out a sliver of some talent) as a fundraiser for a specific organization or cause. Lastly, it would be for something I had not yet requested my friends and family to consider in their generous giving.

Since I knew that this day would come — yes, I do look at calendars and can add — my Decade Dare for my 60th has been very much on my mind for a few years. The good news is that I have many passions and interests so choices have been plentiful. The bad news is that the landscape of need is vast and overly abundant.

Over the next 2 months, I will be sharing many aspects of this journey and all that it encompasses. At this moment, I want to cut to the chase and declare the focus of this Decade Dare and invite you to join me on this path. The easy part is the out of my comfort zone which will be walking 600 km for 5 weeks (approx. 12–15 miles a day) of the Camino de Santiago in Spain. That also covers the time factor. The talent factor is the use of my physical being (as I said, it is just a sliver of talent) and perhaps my sense of direction (helpful in case the yellow arrows disappear). The treasure factor is similar to past Decade Dares as I will cover all my expenses AND match dollar for dollar of any contributions. As always, for anyone wanting to join me in my effort, donations will be tax deductible*.

The area of focus has been a journey in and of itself and I will explain more in the months ahead. I am raising funds for organizations centered on a national truth and reconciliation** process in the United States. I have been engaged in sessions with a diverse group of people. The powerful experience we shared around the potential of truth and reconciliation has inspired me to join their process.

Bryan Stevenson

I have also been inspired by Bryan Stevenson’s work and my inter-actions with him. Bryan challenges us to be proximate, change the narrative, remain hopeful, and be uncomfortable. I am heeding his call. The topic of race in America has become increasingly more important to me as it has become more exposed as a dire issue in our country. I agree with the belief that for us to move forward, we need to acknowledge what is in our past.

As a very privileged white woman, I am well aware that I have much to learn, that my life is dramatically different from American women of color, and that I have been shielded from more than I can possibly imagine. The fact that I am only aware of the ‘dire issue’ recently speaks to my head-in-the-sand and the luxury I have been afforded. I am well aware that as open-minded as I convince myself that I am, that in truth I am not and the level of unconscious bias in my thinking needs to become far less. I am increasingly more aware of the oceans of misunderstanding and lack of knowledge I swim in every day.

I believe we need to change our national dialogue and a truth and reconciliation process is the way to move forward and heal.

There is much to be said, much to be done, much to be questioned, and much to be debated. I have no doubt that every person who reads this will have an opinion. I want to hear those perspectives. As always, I will open my mouth and say something I will be clueless about its meaning, lack of sensitivity, inference, call it what you will. I ask you to consider educating me rather than judging me. Perhaps your teachings and patience will benefit others as well. I think of it as moving the unconscious bias into the conscious and, hopefully, dissipating the bias. I hope we will share this journey.

“True reconciliation is never cheap, for it is based on forgiveness which is costly. Forgiveness in turn depends on repentance, which has to be based on an acknowledgement of what was done wrong, and therefore on disclosure of the truth. You cannot forgive what you do not know.”

–Bishop Desmond Tutu

*Checks are to be written to the Schwab Charitable Fund. Memo line: The Resiliency Fund. In addition to Equal Justice Initiative, I will be doing due diligence on other organizations in this area. A full account including funds, disbursements, mission statements, grant agreements, and objectives will be made available.

**A truth and reconciliation commission is a commission tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing by a government (or, depending on the circumstances, non-state actors also), in the hope of resolving conflict left over from the past. Truth commissions are, under various names, occasionally set up by states emerging from periods of internal unrest, civil war, or dictatorship. In both their truth-seeking and reconciling functions, truth commissions have political implications: they “constantly make choices when they define such basic objectives as truth, reconciliation, justice, memory, reparation, and recognition, and decide how these objectives should be met and whose needs should be served.” According to one widely-cited definition: “A truth commission (1) is focused on the past, rather than ongoing, events; (2) investigates a pattern of events that took place over a period of time; (3) engages directly and broadly with the affected population, gathering information on their experiences; (4) is a temporary body, with the aim of concluding with a final report; and (5) is officially authorized or empowered by the state under review.”

It’s Personal, Part One; The human connection during a human crisis

As the daughter of two generations of refugees, I am well aware that there is always a personal story.

This article originally appeared on Medium.com on May 6, 2016

As the daughter of two generations of refugees, I am well aware that there is always a personal story.

My recent journeys to Jordan and Greece to meet some of the people who have been forced from their homes in the largest wave of migration to sweep Europe since the Second World War reignited my intense interest in hearing their narratives.

When I focus my camera on someone, my mind follows where my eye journeyed. The standard shutter speed of 1/125th of a second activates my curiosity; who is that person, and what is their story? The proliferation of life vests accumulating on the Greek island of Lesbos landfills begs the obvious question; what happened to each person?

In Amman Jordan, I met Siham. She is a lawyer, who fled Syria with two of her three sons, and her daughter. The absent son’s wife and children are with Siham while he tries to make a life for his family in the Netherlands. He traveled through four countries and was one of the 100 survivors in a boat carrying 650 people.

Her youngest son was weeks away from receiving his master’s degree when the regime army took him from their home in Aleppo. After months of no contact, Siham successfully bribed his kidnappers for his return. The next night the family left their home, navigating the constant bombing, eventually reaching Lebanon and then Jordan.

Safa, from Aleppo and now living in Amman with her family, spoke of living in the one back room left of their decimated home in their deserted community. Safa described her fear of going to buy a loaf of bread, as the army would shoot all around her feet to scare her. Her daughter worked in a bank that snipers used for target practice. Within days of quitting, the daughter’s replacement was killed, Safa said. Safa’s 60-year-old husband was in front of their home when the army grabbed him and loaded him on a bus. When he refused to follow his captor’s orders, he was beaten and returned once a ransom was paid.

“My husband is a proud man, he has worked hard all his life,” Safa said. “He was not going to do anything he doesn’t believe in.”

Mohammed, a 21-year-old Syrian, was studying to be a veterinarian. He and his family paid smugglers to bring them to Greece by boat. The photos on his smartphone portray joyous family gatherings and the births of his niece and nephew.

On a frigid night at the Moria refugee camp on Lesbos, Mohammed sang to his friends, other Syrian, Iraqi, Afghan refugees, and a few European and American volunteers. His voice, a bit raspy from a lingering cough, was still strong typifying the sentiment of unity and passion running through the camp that night. While the song was in Arabic, a foreign language to many in the crowd, we all seemed to grasp the meaning, which made us tearful and compelled us to sing and dance.

Asmat, an Afghan in his late 20’s, worked as an interpreter and guide for the U.S. Army in Afghanistan. His English was perfect and he translated Farsi for the volunteers in the Moria camp. Because of Turkey’s border closures, Moria had become more of a detention center than its intended registration center. Considered a “contractor,” he was rendered useless by the shrapnel injury in his leg and received neither medical help nor émigré status from the U.S. Labeled a traitor by the Taliban, he cannot return home. Helping the Americans has put his life in limbo and fear.

In the Piraeus parking lot in Athens, now home to thousands of refugees living in tents, Yana, a 6-year-old Syrian, plays on the weathered, splintered wood of a flatbed truck with her sister and other little girls. There is little for them to play with and the few stuffed animals and one Barbie seem to be more important than is usual for little girls. Her constant sniffling cannot be ignored nor can her dirty hands, face, clothing, and shoes that are far too big for her feet. In the waters behind this rusted and treacherous truck sits a luxury cruise liner waiting to go on to its next port of call.

Salam, a beautiful 19-year-old Syrian girl with sparkling eyes and an engaging smile, sits on a blanket inside the Piraeus terminal with her sister, her sister’s baby, Abuzza, and her cousin. Her mother stayed behind in their small Syrian town to tend to their ailing father. Salam explains in her broken English that she was studying to be a doctor because she wanted to help people. As she guides us through the maze of too many families on too many blankets, it seems that she is trying to help everyone.

Ammar, a scared 5-year-old Syrian, is having his last meal with his parents at Damas Restaurant in Mytilene, the port capital of Lesbos, before getting on the ferry to Athens. The flashlight and balloon gifts are momentary distractions. His loving parents struggle to smile for his benefit. On the floor are all their worldly possessions stuffed in to three knapsacks and two duffel bags. Ammar’s mother, Samar, speaks English, and we discuss the lack of U.S. participation in solving the human and moral crisis.

We walk together, in the cold, to the ferry terminal. As we get closer and as we tearfully hug goodbye, a few glaring men standing nearby ask my new family about me. Samar holds my hand a little tighter and clearly states that I share their perspective, which pacifies the men. Ammar and his parents are anxious and hopeful as they join the long line of people waiting outside for the ferry while the heated terminal waiting room remains unoccupied.

It was the perfect metaphor for what is happening globally; people standing in a cold, barren place waiting for the warm welcome of a new and safe community.

It’s Personal, Part Two; The human connection during a human crisis

My volunteer travels to places like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Palestine, India, and China have, throughout the years, given me heartbreaking exposure to the global human and moral crisis for far too many people.

This article originally appeared on Medium.com on May 9, 2016.

My volunteer travels to places like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Palestine, India, and China have, throughout the years, given me heartbreaking exposure to the global human and moral crisis for far too many people.

There are proverbial glimpses of goodness represented by many non-governmental organization (NGO) workers and volunteers, and by local people who want to help those in their communities. Their stories share a common thread; each person feels compelled to act, in their own way, to belie the abyss of inhumanity.

My recent journeys to Jordan and Greece to learn about some of the individuals who have been forced from their homes in the largest wave of migration to sweep Europe since the Second World War afforded me the opportunity to meet people whose sole attention is focused on the refugees’ plight.

Samar, a 30-something Jordanian lawyer and Human Rights specialist, was disbarred because the Jordanian bar association does not recognize pro bono services, especially for refugees. For 15 years she has worked with refugees, and in 2008 she established a legal aid society. She manages 35 pro bono lawyers who are facing her same professional issues. One of their offices is in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, which was originally designed to accommodate 3–4,000 refugees and now holds close to 40,000; down from a crushing 160,000 at it its height.

Alkis, a Syrian refugee who co-owns a restaurant, Damas, in Mytilene, the capital port of the Greek island Lesbos. Damas is a favorite among the many volunteers and workers for its delicious food, decent prices, personable service, and warm ambiance. Alkis’ personal journey is displayed in his business approach. He employs other refugees and, provides a free meal, at a table in the restaurant, to those refugees en route to the Athens- bound ferry. For many refugees, this is the first meal reminiscent of their former lives in days if not weeks.

Alison, an Australian, now living in London, spends a lot of time on Lesbos. She saw the mounds of clothing being discarded as the refugees had nowhere to launder their wet and dirty clothes. Alison approached local laundry services and together, they created Dirty Girls. They recycle the abandoned clothes and blankets and employ local people who have had little or no work. Once cleaned and sorted, the clothes and other goods are sent to distribution centers so that the refugees can receive culturally appropriate and properly sized clothes. Over 100 tons of materials have avoided the landfills. The United Nations Humans Rights Council (UNHRC) has saved over one million euros by not having to replace discarded blankets.

Rebecca, a beautiful young businesswoman from Sweden, whose partner died leaving her suddenly lost, read about the migrant crisis. She and a friend went to Lesbos to learn more and within hours, they created an all-volunteer organization to alleviate some of the myriad of issues the refugees faced. Their nonprofit, I AM YOU, fought the chaos in the Moria camp of Lesbos with its 3,000 plus refugees by establishing a 24/7 housing program and enlisting volunteers from all over the world. They now operate in Athens and will open in other refugee camps where their services are desperately needed.

The volunteer Spanish lifeguards at Lesbos rescue refugees from boats that are always too crowded and all too often sinking. They lift people out of the water who are wearing reconditioned life vests that have been refilled with water retaining materials which pull them under the sea. The Spaniards have had to make choices that they shouldn’t have to make; which boat do they save when they can’t save them all, which person do they carry on their emergency jet skis when they can’t carry them all.

Negia, originally from Cuba and now living in Athens, is a retired banking executive who was stationed all over the world. Takis, is a 60-something year old Greek businessman from Athens. When the first few hundred refugees came to Piraeus, the Athens shipping piers, from the refugee camps, they and other Greek citizens volunteered to provide food, clothing, medical care, and coordination of services. The Greek government provided empty terminals. As the lead volunteer manager, Negia has gained the refugees’ trust through her empathy and integrity.

Piraeus now houses more than 6,000 refugees in three buildings and numerous outside areas covered in tents with limited sanitation and protection. Every day, more refugees arrive needing all the services attempted by this team of volunteers. Only in the last few weeks have NGOs arrived to help.

These people and the many more I had the privilege to meet and work alongside, reinforced the human connection that is often overlooked. These multinational groups of individuals have sought ways to make the stranger not a stranger.

Tails of Devotion: A Look At The Bond Between People And Their Pets by Emily Scott Pottruck

Tails of Devotion: A Look At The Bond Between People And Their Pets is a coffee table book of letters and photographs of 58 San Franciscan families and their beloved pets -- a visual and profound testimony to the very special relationship between pets and their families.

Tails of Devotion: A Look At The Bond Between People And Their Pets is a coffee table book of letters and photographs of 58 San Franciscan families and their beloved pets -- a visual and profound testimony to the very special relationship between pets and their families. With a five star rating on Amazon, the book presents an interesting dialogue between owner and pet, and vice-versa, through a series of letters that answer the question: "If you and your animals could communicate via paper, what would you say to each other?"

Purchase Tails of Devotion: A Look At The Bond Between People And Their Pets on Amazon.com.