BLOG

Photo by Emily Scott

The 1 Year Anniversary of My Father not Dying

A year ago, my 95-year-old father called me and said, “I’m dying, come here.” This call was a surprise as he and I have been estranged for years and I thought that someone else would be telling me this news. I surprised myself by saying, “On my way.”

Cherry on Top | Photo Credit: Emily Scott

A year ago, my 95-year-old father called me and said, “I’m dying, come here.” This call was a surprise as he and I have been estranged for years and I thought that someone else would be telling me this news. I surprised myself by saying, “On my way.” I was not surprised when he criticized me for not coming immediately, as if I am responsible for the 3-hour time difference in our locations and the flight schedules. His parting shot, “I won’t be alive if you wait.”

He was in his hospital bed the next day. He was giving detailed instructions to the nurses and doctors about how to do their jobs and why they weren’t doing it correctly. I recognized their eye rolls and exasperation as I had been doing that for so much of my life.

My first words startled him and set us on a very different path than our usual can’t-get-past-hello-without-an-argument. I said, “I am here to make sure that whatever you want happens happens, whatever you don’t want to happen won’t happen, I love you, and I am sorry you are in pain.”

That I have been with many people at the end of their lives helped me choose this philosophy. The opportunity to empathize, comfort, and assist if possible at the end of someone’s life is of benefit to both individuals. Had I not been down this path plenty of times before, I would have been at a loss for my father and for myself that day in the hospital.

The next two days were a combination of hand holding, assisting in filling out paperwork, discussion and implementation of end-of-life choices, encouraging words to the medical personnel (rather than those of admonishment), ordering takeout for him to enjoy (and as expressions of gratitude for the medical staff), and some crying and laughing.

Magic happens when you least expect it. My father told me he was ready to go. He wanted to go. He had enough. I pushed back and he didn’t budge. So, I brought the doctor in and said, “He wants to go, what do we need to do to make sure all his wishes are met?” For over an hour we went through every question and every document. As his daughter who knows a bit about how his mind works, I could offer explanations and examples that helped him understand the paperwork and what he was signing off on. When we finished, he turned to me with a look I had not seen before and proclaimed, “You are my daughter after all.”

Translation: I am not exactly like my mother, whom he divorced 53 years ago, and their mutual dislike of each other remains. That his smarts and wisdom flow through me as well.

Truth: This is my father’s first time in over 40 years that he has approved of something I have said or done and I knew that this was his way of expressing that sentiment (not the best way to lovingly express approval, in my opinion, but there you have it).

Since returning home, we have skyped frequently and each conversation begins the same way:

Me: “Hi Dad, how are you?”

Dad: “Not good. This is it. I’m dying.”

Me: “I know. And I am really sorry you are in pain. And I love you.”

Six months ago, I flew back to Massachusetts to visit him. As always (always being my entire life), he spent hours giving me his theory of DNA programming even though I have heard it so often I could recite his theory back to him. This time there was a difference in that experience. I asked him if he wanted me to only listen or did he want me to respond and if he wanted my verbal engagement, was he prepared to listen. Our dialogue pattern altered as I listened with the recognition that it was importance for him to get his thinking “out there.”

My father also let me take care of him. I cooked, freezing much of it for future meals. I had him instruct me how to make “his” salad dressing even though I have spent years making it on my own. The instinctual recognition that we all want to feel needed and heard was never more obvious to me than during that weekend.

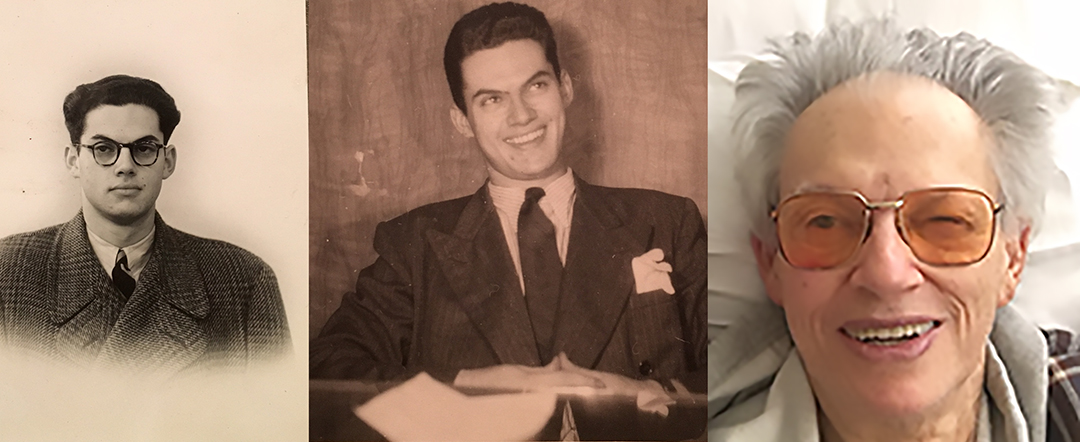

We spent hours talking about his life, about his escape from Europe during WWII, the murder of my relatives at the hands of the Nazis, his time in Cuba, and his eventual immigration to the United States. While I knew much of his story, many pieces of the puzzles emerged. He handed me letters from his father – the grandfather I never met - that had been smuggled from Czechoslovakia to Hungary, readdressed and then mailed to my father in France where he attended college. I had never seen these before and had no idea of their existence. The detailed accounts of what was happening at that time in Europe and to my ancestors on the almost-sheer, crumbling paper was one of those spine-tingling moments.

On the one year anniversary of his first call, I skyped my father and said, “Happy one year anniversary of not dying yet.” He laughed. We actually laughed together. We both know that he is dying. He is 96 years old, of course the end is near. That we could talk about life and death for this year has been more life affirming than sad. That we had our time to discuss and put aside some of the past differences has been more therapeutic for both of us than the years of counseling we have probably both done to heal ourselves from each other.

What this past year has done is give both him and me the opportunity to see each other and hear each other differently. He got to see me as an adult, I got to learn more about his childhood and inner struggles.

Reconciliation had seemed improbable. We both tried and we failed many times. Enough times to eventually stop trying. My loving stepfather had offered me sage advice in my late 20’s; keep trying until you are more than completely satisfied that when your father dies, you will have no regrets. I did and years ago, I was satisfied that when he died, I would have no regrets. Nothing else needed to happen. What did happen this past year was unexpected and magical. As my father would say, “the cherry on top of the hot fudge sundae.”

Peter Scott